Entrance to Cascade Canyon

Thurman: Have you seen my advent calendar?

Willie: What the fuck is it with the advent calendar?

Willie: What are you so obsessed with that goddamn thing? The story sucks anyway.

[Feels badly for yelling at Thurman]

Willie: I think I saw it out there in the hallway.

Thurman: Really?

Willie: I think so.

[Thurman retrieves calendar]

Thurman: Looks like someone messed with my advent calendar.

Willie: What are you talking about? Let me see.

Willie: Nobody messed with it. It looks fine.

[Thurman opens calendar]

Thurman: There's a candy corn in this one.

Willie: Well they can't all be winners, can they?

~Bad Santa (2003)

There's a discernible "wart," "bump," "protuberance," or whatever you want to call it along the dramatic ridgeline leading south from the summit of Ontario Peak. It's not a recognized "peak" in its own right, but it is prominent enough in relation to the rest of the ridge to be instantly recognizable from both near and far. Peakbagger refers to it as a "provisional" peak. Everyone I know just calls it the "Turtle's Beak," so named because (i) it does somewhat resemble a terrapins's schnozz, and (ii) the alter-ego of the first guy reputed to climb it was named "Turtle."

When Turtle first climbed the beak, he approached it from the north. After scaling Ontario Peak, he then dropped along the ridgeline south, roller-coastering over a series of humps before finally achieving the objective. It was an arduous overnight affair, and along the way he encountered a sea of buckthorn and other nasty flora.

Since that first ascent, a handful of other hardy souls I know have visited the Beak. But instead of following in Turtle's gigantic footsteps, these folks discovered an alternate route that avoids the impenetrable buckthorn of Ontario's south ridge. The approach also shaves miles off the "standard" route. This "shortcut" involves going right up the steep gut of Cascade Canyon to attain the ridge immediately north of the Turtle's Beak. It's a 3,000' scramble up a wild and trail-less canyon that involves some route-finding and class 3 exposure.

Cascade Canyon is a notable destination for rock-hounds. Not only can corundum crystals be found here, but it is reputably one of the few places in the United States where one can find rare lapis lazuli. Getting to the veins of the uncommon mineral is quite a challenge, however because the deposits are located in the steep, remote, and rough upper stretches of the canyon. Mining for the semi-precious stone has occurred here in the past with limited degrees of success, but those days are now gone (although the north fork of the canyon supposedly still harbors the visible remnants of one of these operations). Amateur collecting is now all that occurs here.

The Iron Hiker, an accomplished peakbagging friend a mine, determined that it was time to visit the Beak and he invited me along. He'd done his due diligence and spoken to others who had ascended Cascade Canyon before, and his plan was to essentially repeat their efforts. Always game for an adventure in the forest, I agreed to the join in on the fun.

We met at the parking area at Barrett-Stoddard Road at 6:00 a.m. and soon headed off for parts unknown. The morning was clear and cool as we walked easily along the well-maintained fire road, crossing the still-flowing creek at North Fork Barrett Canyon and passing the intriguing Gingerbread House. Beyond the last reclusive home in the canyon and a forest service gate, the road leaves the forest's protective canopy to burst out into the open, permitting unique views of San Antonio Canyon, Sunset Peak, and Lookout Mountain.

The Beak (center-right) from Barrett-Stoddard Road

Starting Up Cascade Canyon

A short distance later, we were at the obvious entrance to Cascade Canyon which didn't look particularly inviting. We paused briefly to double-check our bearings, put on our battle armor, and headed in. Initially, there were signs here and there that others had been in the canyon. Most likely rock-hounds. We followed their faint trails as best as we could until they eventually petered-out entirely. Then it was just a matter of following the drainage straight up the canyon.

But this was no easy task. There is no established route so we were basically just feeling our way up the drainage. And the canyon is a continuous obstacle course of dislodged boulders, thick dead-fall, impenetrable brambles, spider webs, and poison oak. Progress slowed to a crawl as we climbed over and ducked under downed trees, hopped from unstable rock to unstable rock, and delicately danced and shimmied as best we could around, over and through the ubiquitous stands of poison oak.

After what seemed like a couple of hours of moving but not making much progress, we hit a veritable wall of thorny blackberry bushes. To our right, the hillside opened up some affording an opportunity to leave the hostile canyon floor. We took that opportunity, optimistic that it would allow us to bypass the blackberry rampart. But not long after that, our hopes were cruelly dashed when we cliffed-out high above the canyon bottom. We could look down and see exactly where we wanted to be, but getting there was too treacherous. Back at the blackberry wall, we re-assessed our situation and decided it best to abandon the effort. Begrudgingly, we rock-hopped and brush-bashed our way back to Barrett-Stoddard Road.

Since it was still early and we felt the need to at least go home with a participation trophy, we continued south on Barrett-Stoddard Road to climb nearby Stoddard Peak. The road-walking was easy and chatter distracting and we were soon at the saddle that separates San Antonio and Stoddard Canyons. Here, a well-established use trail peels off to the right to ascend the short ridgeline on which Stoddard is the third knob to the south.

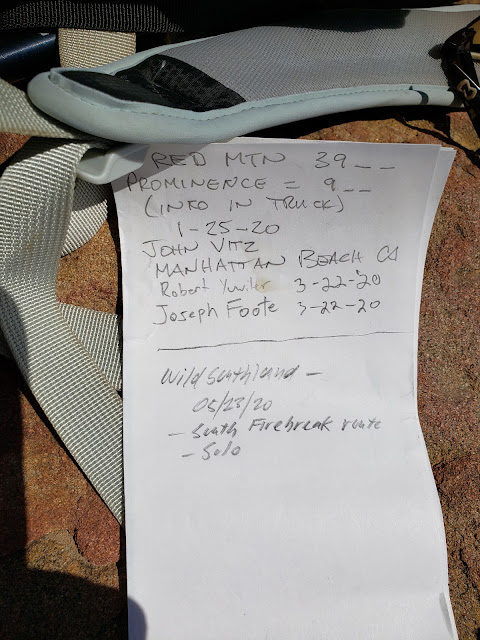

After passing some interesting rock formations near the middle bump, we arrived at Stoddard proper where we cooled for a bit, had some snacks, and absorbed the fine vista. There's a triangular witness post on the summit, but we didn't find a register. We did, however, find a red ant colony, some of which were of the flying variety. And the voracious little bastards didn't appreciate our presence and started stinging. Or at least they started stinging me. The Iron Hiker, apparently ill-tasting and immune from red-ant scorn, sat bemused as I stripped off clothing to rid myself of the demonic and cantankerous little pests.

Eventually, he (and I) had had enough and we started back. The road walk went quickly, but less so than on the way out. Or so it seemed. It's always that way for some reason. Maybe it's the Christmas-Day excitement of going out that makes the miles pass so effortlessly, and the dread of returning to reality that makes them creep by so slowly. Regardless, back at the previously vacant parking area, cars now filled every available nook, cranny, crevice, space, and spot. A canyon resident was there sweeping the dirt off the "No Parking - Fire Zone" markings on the pavement and barking at scofflaws who responded with everything from indifference to disdain. I chatted with her some as she put her broom into the back of her SUV. She confirmed what I already knew: since the pandemic began, and bars, restaurants, movie theaters, bowling alleys, and other amusement establishments all closed, the canyon has been overrun by what a grumpy acquaintance of mine disparagingly calls the "filthy casuals." And it's having a real and negative impact on our open spaces. Trash, graffiti, and other urban and suburban-type fuckery is now a regular part of the outdoor experience courtesy of those who have spent the better part of their existence indoors.

A vaccine for Covid can't be developed and deployed quickly enough so that these indoor refugees can finally get back where they belong and they really prefer to be: indoors.

The almost "standstill" speed represents the time spent in Cascade Canyon. Very slow going.