Thorn Point and Mutau Flats

Sometimes I wonder what I'm gonna do

But there ain't no cure for the summertime blues

~Summertime Blues, Eddie Cochran

So I'll meet you at the bottom if there really is one

They always told me when you hit it you'll know it

But I've been falling so long it's like gravity's gone and I'm just floating

~Gravity's Gone, Drive By Truckers

As you can tell from looking at the large gap between posts here, I haven't been inspired to write much lately. The process has always been a laborious challenge for me, but now it's a real struggle to even put pen to paper. Being the opinionated bastard that I am, it's not that I don't have anything to say. Just ask the people around me. They know that I'm rarely at a loss for words. And they're probably grateful for the respite from my constant yammering and bloviating. But the whole thing weighs on me. The muse has abandoned me without notice and everything I try to write now feels forced and inauthentic.

But these are strange and frightening times we're living through. People are fucking dropping dead from an enemy that can't be seen or fought. We're all wearing face-masks at the grocery store for fear of contagion. I haven't shaken a stranger's hand or given someone outside of my bubble a hug in months. I'm maxed out on vacation accrual, but can't go anywhere to use it. The restaurants and malls are empty, but the trails are packed with people, graffiti, and trash. And politicians' promises notwithstanding, it don't look too much like things are going to get materially better for the average person any time soon. So yeah, things are kind of fucked up right now. For that reason, I guess my muse can be forgiven for perhaps having a case of the pandemic blues.

In an effort to get out of my funk, I decided a day in the woods would be good for my soul. So last Friday, I played hooky from work and headed for San Rafael Peak, a seldom-visited summit deep in the Sespe Wilderness.

The Iron Hiker joined me on this adventure. The original plan, devised by the ferrous one, was to hike Hines Peak and Cream Puff from the eastern terminus of the Nordhoff Ridge fire road. To do that, we needed a permit from the Forest Service. But that plan was foiled when fires closed the entire Los Padres for a spell and permits became unavailable. Then, the normal, seasonal closure of the Nordhoff Ridge road went into effect guaranteeing that we would not be doing Hines Peak the easy way until next spring. So we went searching for a remote, uncrowded, and challenging alternative. San Rafael checked all of those boxes nicely.

Morning Commute

Cattle Drive

We met early at the entrance to Grade Valley Road and then drove the 10+ miles south on a washboard dirt road to the Johnston Ridge Trailhead. Sunlight peaked through the forest canopy as we went and I kept an eye out for wildlife as the conditions seemed ripe for a sighting or two. Unfortunately, all we encountered was a herd of bovine blocking the road that weren't in any particular hurry to cede ground to us. But being the superior beings that we are, we dispatched the dumb beasts with a couple of blares of the horn and we were on our way.

The trailhead parking area was vacant. We were the only ones in the forest. We gathered our gear and started off, heading southeast on a well established trail that skirts Mutau Flats to the south as it drops about 200' in elevation to Mutau Creek. The word "Mutau" features prominently in this part of the forest. Although linguistically it sounds like it could be Chumash in derivation, it's actually the last name of a cantankerous old horse rustler who homesteaded these parts. Old Man Mutau, who settled in the area that is now the flats, was a known ally to horse thieves who moved stolen horses along the Horse Thief Trail from southern Ventura County to Kern County. Mutau, whose homestead sat right along the trail, permitted rustlers to use a canyon on his homestead (appropriately named "Horse Thief Canyon") to graze purloined horses before they were moved off to Tehachapi to be sold to work crews who were constructing the railroad from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Old Man Mutau met his maker at the flats that now bear his name when was ultimately shot and killed there.

No Country for Old Men

Mutau Creek

Breathing Room

Moo-tau

Mutau Creek was still flowing some, so we splashed through and started up a minor drainage that climbed to an obvious saddle at 5,729'. Along the way, we found a mylar balloon with a bright pink boa that we would retrieve on our way out. (PSA: stop releasing mylar balloons into the air people!) At the saddle, the trail continues east, dropping into the Little Mutau Creek drainage. Here, however, we abandoned the trail, opting to go cross-county in a southerly direction over a serious of bumps that lead to San Rafael Peak.

The Sierra Club says that the navigation along this part of the route is "difficult," but we found it to be pretty straight-forward. At one stage, we wandered slightly off-track, going too low on the northeast flank of Pt. 6,408, but we quickly righted ourselves by making a steep climb back to the ridgeline which has expansive views of Hot Springs Canyon and the Sespe Creek drainage. We then traversed one final minor bump and made the steep climb to the summit.

Going Off the Grid

Dragon's Back

St. Raphael

Home of Hot Springs

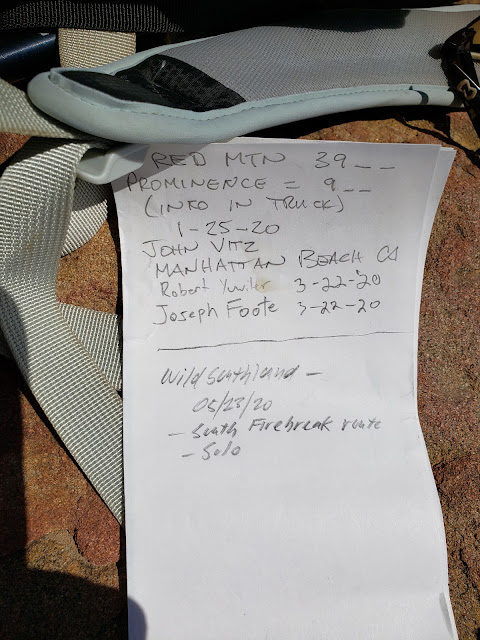

Atop San Rafael we had 360-degree views of the entire Ventura County backcountry. Cobblestone, Topa Topa, Devil's Heart, Hines, Chief, Thorn Point, Haddock, Reyes, and Pinos are all clearly visible from summit. We logged our appearance in the summit register which dated back to 1974 and then lollygagged in the warm sun and tried not to share our snacks with a bunch of insistent hornets that magically appeared every time a plastic baggie or foil was opened.

Then it was time to go. Days are short this time of year and light a precious commodity. We were well equipped with lighting, but really didn't want to have to rely upon it. So we retraced our steps back to the trailhead and began the long drive back to the reality of life in a pandemic. I can't say that this little adventure cured my pandemic blues or broke my writer's block, but as the old saying goes, "sometimes you just need to go off the grid and get your soul right." And my soul was right on this day.

Cobblestone Views

Topa Topa and Devil's Heart

Summit Pano

Thorn Point, Haddock and Reyes

Going Back Home